When the Carnegie Classification System was created in 1973, it had a fairly modest goal: describe and group higher education institutions according to the types of degrees they conferred, so that colleges and universities could be more effectively researched. While over time, the system expanded in order to take into account additional factors (such as including the number of degrees awarded, the level of research activity, and the size of the institution), the categories have remained relatively static since their introduction: colleges are sorted into groups based on the highest level of degree they award (i.e., Associate’s Colleges, Baccalaureate Colleges, Doctoral Colleges). Within these larger categories are subcategories, the most well-known being the R1 and R2 designations assigned to doctorate-awarding institutions based on their level of research.

Though originally intended to act as neutral descriptors, the classifications were almost immediately used for other purposes. Classifications, for example, provide the foundation for the U.S. News & World Report rankings; in the U.S. News system, only doctoral universities (which would include all R1 and R2 institutions) are labeled as “national universities.” Similarly, a R1 or R2 classification is associated with a higher level of federal funding for institutions’ research, and higher classification can therefore help attract students, prospective faculty members, and donors.

Thus, increasingly, colleges and universities have chosen to invest resources into moving into the R1 and R2 categories, often at the expense of the institution’s mission. Speaking to Sara Gast, the deputy executive director of the Carnegie Classification Systems, she explained: “Institutions may want to be doing a whole bunch of other things, but they end up spending a lot of energy and time on pursuing a research classification because of the prestige it gives or the sense of the ability to open up additional funding dollars.” With that in mind, The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching and the American Council on Education have begun reimagining a new Carnegie Classification system that will “better reflect the public purpose, mission, focus, and impact of higher education.” Although what, exactly, the new classification system will look like is still uncertain, one goal is to reassess how colleges are being classified to better capture the work that’s being done at universities, including how well they’re serving their students.

That’s where the new Social and Economic Mobility Classification comes in. The new classification will, as the name suggests, categorize higher education institutions based on how well they’re serving a diverse range of students and could be evaluated using measures like completion and retention rates, earnings post-completion, etc. “To the extent that we know the classifications do drive a normative behavior,” Gast explains, “we are hoping to encourage and increase that behavior to be on student outcomes and student success as opposed to just on research, although there will still be a research classification.”

How the Social and Economic Mobility Classification will fit in with the current system is still being discussed, but what seems clear is that it will not act as a “tacked-on” measure but will be fully integrated into the classification system. According to Gast, “Are those parallel? Are they interwoven? That is a little bit of the question. Still, we are still wrestling with ourselves, because we really do want to group similar types of institutions together, and we’re just trying to decide the best way to do that.” One option, Gast explains, although this is not definite, “is thinking of it more like a Myer-Briggs type approach, where you might get multiple labels, and it’s not that one is not better than the other. They are just different, and they’re describing different aspects of an institution.” This last point is important to emphasize: these classifications will not act as rankings. As Gast says, current economic and social mobility indexes that exist for higher education institutions are typically rankings, “so they’re trying to put a number on the institution, and they generally group all institutions together into one big bucket, so I don’t really know what it tells the institution. It doesn’t encourage any sort of collaboration or learning, and our hope is that the power of a classification is to identify institutions that are doing better on some number of things, and then to create learning communities for them, to improve on others, or to share best practices, or to otherwise be organized.”

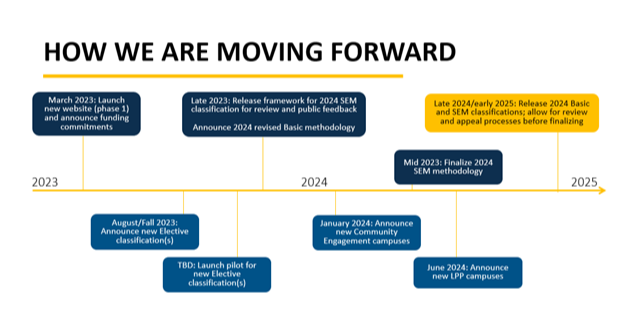

What seems clear is that Carnegie is being very intentional about the changes that they make to the system. In my conversation with Gast, I asked about how the new classification system might affect institutions like women’s colleges or primarily minority-serving institutions, whose graduates may face more discrimination in the workforce. “We know that earnings and opportunities aren’t always equal, and we have a couple of groups that we’ve been bouncing ideas off of,” Gast explained. “So one is our institutional roundtable to our college presidents, who are telling us, ‘here’s something you might want to think through.’ And then our technical review panel, who have been particularly intentional about this question, because we’ve been looking at the data. For example, one of the ways we were looking at earnings data initially, when you’re seeing some of the outcomes, the take-away would have been for women’s colleges to enroll more men. We don’t want to have that be the takeaway, so we’re looking at various mathematical ways that we can consider regressing or adjusting, based on census data or state-level data or even city-level data to account for that.” To further allay any concern administrators and staff may have, Carnegie has also shared a projected timeline of the path forward, which includes ample time for schools to give feedback based on new classifications.

Looking ahead, although much remains uncertain about the 2024 Carnegie Classifications, there’s much to be optimistic about. Institutions will have the opportunity to re-examine what they’re prioritizing and, in some cases, realign themselves with their missions. Classifications will be able to more accurately capture the important work that’s being done on campuses, which will, in turn, empower students to make more educated decisions when choosing a college.