fizkes/Shutterstock

As a leader in higher education, what assumptions do you make about your employees’ motivation? Do they believe in the work of the organization, or are they punching a clock for a paycheck? And how does this shape the way you manage them?

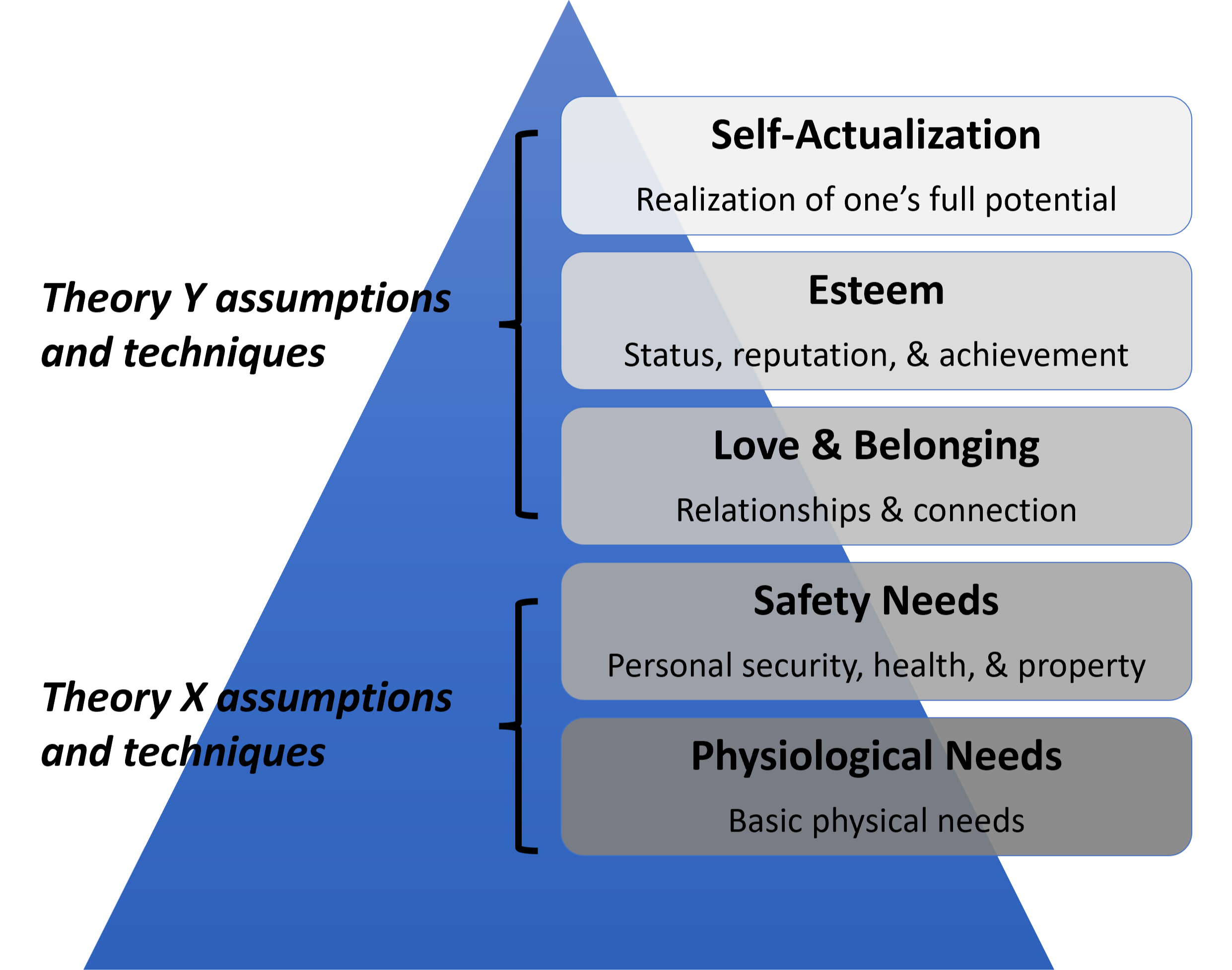

Seventy years ago, Douglas McGregor wrote about this classic motivational problem in “The Human Side of Enterprise.” He contrasted two types of managers: those who follow “Theory X” and those who subscribe to “Theory Y.” Theory X managers believe that employees naturally dislike work, are self-centered, and resist change. The role of the manager is to motivate them through sticks and carrots. On the other hand, Theory Y managers presume that employees naturally want to do their work, are self-motivated, and will seek out responsibility if given the chance. These managers focus more on giving agency to their employees, building relationships, and ensuring good alignment between the organization’s and employee’s goals, believing that ultimately, through more freedom, the full capacity of people can be tapped.

McGregor quipped, “The answer to the question managers so often ask of behavioral scientists ‘How do you motivate people?’ is, ‘You don’t.'”

Theory Y is an alluring idea, a sunny outlook, and a glass-half-full view on human nature. And it has taken over higher ed — and the workplace more generally — in a “work-from-home” world. Indeed, my own research has focused on tapping into this theory through the relationship of job crafting and employee commitment in higher education. A theory Y manager is the kind of boss everyone wants to work for, right? Nobody wants a micro-manager.

But agency is only one end of a two-ended stick that managers pick up. Neither Theory X nor Theory Y approaches have the potential to motivate employees by instilling agency and accountability in all situations. McGregor acknowledged as much when he said the need for one theory over another is much more related to where employees are on Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. In situations where physical and security needs exist, such as in a crisis, X managerial behaviors are required. When lower-level needs are satisfied, and belonging, esteem, and self-actualization needs occur, Y works much better.

Most studies confirm that the vast majority of faculty and staff in higher education are internally motivated. They believe in the mission, crave the challenge, and simply like their work. That their paycheck is often so meager by comparison to other professions is a testament that the work itself is rewarding. Theory Y is by far the preferred managerial approach for most workers. This is especially true for faculty who love the autonomy they are afforded and view the university as a network of equals rather than a hierarchy.

In reality, those who lead faculty and staff need to be prepared to use both X and Y techniques with those they lead. Here are just a few situations where X techniques may be needed over Y:

- Times of crisis. This can be a budget, health, or other emergency. In a crisis, employees’ feelings of safety are threatened, and they look more strongly to leaders in their hierarchy for security and motivation.

- New or inexperienced employees. Until employees feel comfortable with their new role, they look to their direct line leaders for tangible support and may need to be helped through positive and negative reinforcement to gain confidence in their duties.

- Misbehavior. Perhaps the most unwelcome time for Theory X techniques is when discipline issues manifest. Faculty leaders may need to resort to top-down consequences and improvement plans that appear as micro-management to difficult employees.

- Loss of focus. In addition, when employees drift too far from the mission or purpose, a normally hands-off manager may need to refocus their work. For example, a faculty member at one institution who lost control of her research agenda needed to be put on an improvement plan until she realigned her work.

On the flip side, employees working in a mostly X environment could benefit from more Y techniques. Staff members in higher ed often work in a hierarchical structure with less freedom and tighter command-and-control. Why couldn’t these employees be offered more flexibility in their working hours or choice of responsibilities? Job crafting offers a helpful framework for designing their ideal working conditions. In addition, bringing these employees into the creative and innovative process through structures like employee think tanks, proposal processes, change symposia, or other ideas unlocks the intellectual capacity of all organization members and creates commitment.

Both X and Y traits are needed to meet the motivational needs of employees. One provides the backbone and the other the heart of a manager’s approach to their people. After McGregor’s death, thinkers such as William Ouchi would try to blend these views into a “Theory Z” with a balance of informal control and structure. Simply throwing open the door to agency for those unprepared to handle what they will find in the next room over can undermine an individual’s ability to succeed and derail an organization from achieving its mission. Leaders need to be ready to use all the tools at their disposal.