by Lindsay Till Hoyt, Ph.D.

zimmytws/ Shutterstock

Student mental health and well-being are campus-wide priorities at most institutions. In a survey of over 400 college presidents conducted by the American Council of Education in 2019, 80% of respondents indicated that mental health had become more of a priority on their campus than it was a few years ago. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, over half of presidents said they needed additional tools to help them address college student mental health on campus.

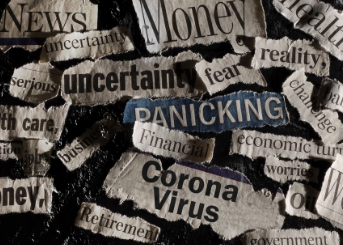

College student stress is usually considered at an individual level (e.g., financial stress, grades, relationships), and therefore the tools to address these stressors are also individual (e.g., counseling, peer tutoring). However, given the dramatic increases in mental health problems reported in the last decade, institutions of higher education also need to consider the macro-level forces in which our colleges are embedded. The systems, cultural phenomena, and political events unfolding beyond campus have important implications for individual students’ well-being.

My colleagues and I defined sociopolitical stress as the intense feelings and experiences people have that stem from awareness of, exposure to, and/or involvement in political events and phenomena. Importantly, sociopolitical events may exacerbate intense stress caused by systemic racism, economic strain, sexism, or other forms of marginalization. For example, we studied college students before, during, and after the 2016 and 2020 U.S. presidential elections, uncovering unique patterns of physiological and psychological stress based on students’ social positions, identities, and experiences. From a national election, executive order, or supreme court ruling to a local policy or event, students may display a variety of reactions. Sociopolitical stress can exacerbate feelings of anxiety, depression, or isolation and negatively affect students’ academic and health trajectories. On the other hand, sociopolitical stress can also function in positive ways, motivating students to connect with others, learn about civic processes, and engage with their communities.

Below, I highlight three areas where institutions of higher education can think about integrating both new and existing practices to help students cope with sociopolitical stress and conditions of inequality. Each section includes a set of examples meant to serve as a starting point for faculty and administrators to discuss barriers and facilitators to creating effective, equitable, and sustainable support for students.

1. Acknowledge that macro-level forces affect individual students’ well-being.

Acknowledging national or local events could go a long way toward promoting students’ mental health. In some cases, faculty and administrators can plan for salient events ahead of time. For example, elections and inaugurations are set dates that can be worked into the academic calendar. Some faculty, especially those in the liberal arts or social sciences, may be able to integrate readings or discussions around sociopolitical stress (and resources to cope with stress) into their courses. Other faculty, regardless of disciplinary training, can strategically move key assignments or exams away from these dates and/or incorporate an absentee policy that includes mental health day(s), which has seen increasing support across grade schools, higher education, and workplaces settings across the country. Colleges and universities can also offer campus-wide events or speaker series related to national or local events. In particular, institutions of higher education should invite speakers who have experienced marginalization themselves (e.g., due to discrimination based on their race/ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, disability), who can speak to inequalities in well-being and relate to those underrepresented students on campus who often experience heightened sociopolitical stress.

Beyond planned events, institutions of higher education must also consider how to react to current events in real-time. Within the classroom, faculty members can scaffold inclusive conversations about political events, offer a safe space to listen to students’ concerns, and/or refer students to relevant resources. Indeed, faculty members are often on the front line of student mental health. Institutions of higher education should invest in these classroom experiences by offering training around effective communication, active listening, and de-escalation techniques for moderating difficult conversations. Additionally, campus leaders may send messages to the entire student body or post statements on social media in response to anxiety-provoking political news (e.g., policy change) or tragic events (e.g., mass shooting), to acknowledge macro-level stressors and share mental health resources.

2. Invest in innovative, youth-informed, culturally sensitive resources to support students’ mental health and well-being.

Most colleges and universities have a counseling center, as well as a variety of wellness resources that may include a Title IX office, center for substance abuse prevention, campus ministry, or mentoring programs. However, these services may lack culturally sensitive practices, are often limited to traditional business hours (e.g., students may be referred to campus safety or 911 after hours), and have limited capacity (e.g., most counseling centers only offer short-term therapy). Unfortunately, this means that many students have unmet needs, especially when demands on existing wellness resources are greatest. For example, LGBTQ students may not have access to culturally responsive resources during times when their basic rights are being debated in the media. Black young people, who experience the highest rate of harassment by the police, may be less likely to reach out for or receive help during times of crisis if the university’s policy is to alert campus security on evenings or weekends.

A key way for institutions of higher education to build stronger support networks is to design innovative solutions in partnership with students from diverse backgrounds across campus. Student-led innovation in campus mental health — including peer support programs, awareness campaigns, advocacy groups, technology start-ups, and affinity groups — is promising but often lacks support and funding. Many great examples are described in a recent report by the Collegiate Mental Health Innovation Council, which highlights the impact of disability supports, peer support, and technology on student mental health and the role of student leadership in each of these areas. University leaders can help facilitate and fund programs on their own campus — as well as help connect students, faculty mentors, and staff working on the same issues across the country. Overall, listening and learning from our students will play a key role in constructing the future of wellness on campus.

3. Create supportive spaces that promote college students’ civic development and engagement.

College is a unique environment for civic participation, especially for emerging adults. Many young people are exposed to new ideas as they continue to form their identities and values in relation to society. However, unequal access to civic education and opportunities by socioeconomic position starts in adolescence and can both perpetuate civic and social power inequalities through adulthood. This is important because, within supportive contexts, young adults’ civic engagement can be a powerful tool to cope with sociopolitical stress or conditions of inequality.

Many colleges already offer diverse civic engagement opportunities ranging from classwork and clubs to student-produced media to coordinated volunteering. However, institutions of higher education should also prioritize teaching the language of inequality as part of their core curriculum, fostering discussions that make students critically reflect on systems of privilege and oppression within their institution and beyond. Further, colleges can bolster civic efficacy by offering classroom experiences, workshops, or online resources that teach or reinforce civic skills, including communication, debate, and understanding rights around protest and civil action. For example, faculty or staff could co-create petitions or events in partnership with students as a way to scaffold civic development. Another way that colleges can promote civic values, beliefs, and skills is through community-engaged learning or youth participatory action research (YPAR). Community-based courses or YPAR can empower students, help students cope with sociopolitical stress through social support and shared action, and help bridge the college/university with neighboring communities.

Approximately 42% of all young adults in the United States under age 25 are enrolled in college. We also know that these Gen Z young adults (i.e., youth born after 1996) are more worried about our nation’s future, report more stress than adults about issues in the news, and have poorer mental health than all other generations. Therefore, institutions of higher education play a pivotal role in influencing and empowering Gen Z students to face increasing sociopolitical stress in ways that can promote their long-term mental health.

Disclaimer: HigherEdJobs encourages free discourse and expression of issues while striving for accurate presentation to our audience. A guest opinion serves as an avenue to address and explore important topics, for authors to impart their expertise to our higher education audience and to challenge readers to consider points of view that could be outside of their comfort zone. The viewpoints, beliefs, or opinions expressed in the above piece are those of the author(s) and don’t imply endorsement by HigherEdJobs.