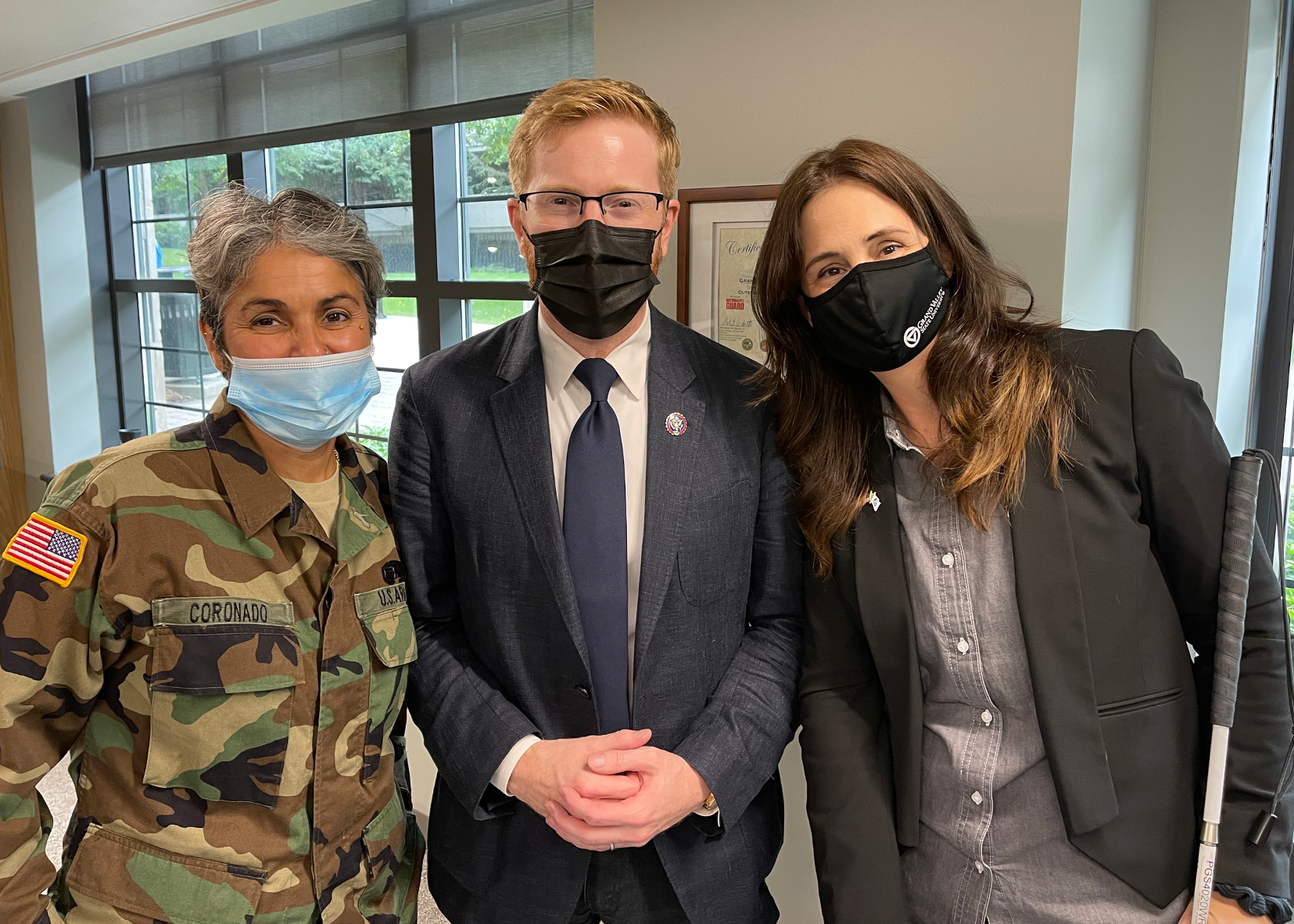

Photo by Jill Hinton Wolfe

I know all about awkward — being visually impaired means I deal with awkwardness in almost every stranger interaction I have.

October is National Disability Employment Awareness Month, so I want to take the opportunity to talk about what it means, to me, to be a blind person working in higher education. Currently, I serve as the Military and Veterans Resource Manager at Grand Valley State University near Grand Rapids, Michigan.

People try to shake my hand, and I just keep talking. Often, I run smack into displays in stores or crash into folks coming out of the restroom. The worst is explaining to people why I need a ride to an event because I can no longer drive.

The other day, I actually put on my pants backward and almost walked out the door that way.

But with time, my visual disability is something I’ve had to learn to figure out. Because the alternative is to sit at home, socially isolated, collecting social security. And that’s just not me!

How I Became Blind

I wasn’t always blind; in fact, it’s only been in the past six months, or so, that I’ve been forced to come to terms with the fact that my eyes don’t work anymore. Of course, I’ve known since 2017 that I would go blind, but there’s nothing like almost killing a stranger with your minivan on the way home from the grocery store to make things real.

It was in 2017 when I was diagnosed with retinitis pigmentosa (RP). This rare, incurable genetic disease causes the cells in my retinas to slowly go dark, like a jumbotron with its lightbulbs burning out. Although my RP has nothing to do with my military service, the lessons I learned in the Army, around adapting and overcoming, have come in pretty handy.

It’s taken me pretty much all of the last four years to get used to the idea that I am, in fact, blind. Pre-2017, I sat where you now likely sit. I never had to ask strangers for help or explain why I needed certain accommodations to do my job. I never whacked anyone with my cane or had to explain why a cure wasn’t really in the cards for me (and why focusing on a cure was actually unhelpful).

I never had to yell “I’m not drunk!” in a conference room after I tripped over my chair (and unlike in my twenties, now it’s actually true).

So, think of me as your ambassador, your guide/scout to help you learn how to interact with people who have a whole range of disabilities — from physical disabilities (like paraplegia), to learning disabilities (such as dyslexia), to hearing/vision loss, to neurodivergent disabilities (like autism).

Talking About Disability is Awkward

Whether it’s a student or a colleague, talking about disability is uncomfortable. Most often, that awkwardness comes from the fact that we don’t want to offend people, and we’re scared that we’ll say the wrong thing. This is admirable.

But not talking about disability is what leads to people feeling invisible — and the LAST thing any of us wants to do is make our students or colleagues feel invisible.

So how do we balance being open and honest without being overly “politically correct,” which is cringe-inducing for all of us?

I’ve found two key mindsets are helpful:

- Avoid unintentional/well-meaning — but ultimately patronizing — language.

- Simply check-in with the other person’s preferences. ASK!

Now that I think about it, talking to people with disabilities isn’t all that different than talking to veterans. The best course of action is to keep the focus on the person, and not on their “identity,” and just respectfully asking people about their preferences will rarely steer you wrong.

5 Tips for Talking to Disabled Students or Colleagues

Here are a few simple guidelines for removing the awkwardness from conversations around disability.

Don’t panic if you say something unintentional.

If you use idioms, or other figures of speech, that vaguely reference the person’s disability (i.e., “blind luck”), don’t panic! Just keep calm and move on in the conversation. Chances are they didn’t even notice!

Once you get to know a person, it’s okay to ask them about their experience.

No one likes to get the third degree on a “first date,” so avoid diving right into the disability conversation during small talk when you first meet.

After you’ve chatted and learned more about the person, you may want to ask them what they want to be called – i.e., “a person with a visual disability” or “blind” (personally, either one is fine with me). But you also need to respect their privacy if they don’t want to talk about it, and don’t take it personally if they decline to tell you what happened.

However, if there are situations where you need to ask a question that involves making them more comfortable or included, do that. Keep it simple! “Will the meeting room work for our coworkers with ______?” or “I’m interested in learning more about what it’s like for you to commute to work with _______?” are both excellent options.

Don’t tell people you admire them or find them inspiring for doing the same things everyone does.

It is patronizing to tell people with disabilities that you find them “inspiring” just because they do something simple, like getting out of bed or showing up at work. If you’re going to say it, tie it with a significant accomplishment (similarly as you would with someone who didn’t have an obvious disability).

Most people with a disability find the word “handicapped” derogatory. Avoid using it.

There’s a whole debate about “person-first” language (i.e., “person with” or “person who has” before mentioning their condition) versus “identity-first” language (i.e., putting their identity as a disabled person first “I am a blind woman”). The point is to reduce stigma and ensure that disabled people get the same treatment as everyone else.

Whatever you do, try not to say handicapped, cripple, or any other archaic term. And if you do let it slip (it’s happened to me), apologize, if appropriate, and move on.

Don’t ask about a cure.

I hate it when people ask me about raising money for a cure. Sure, there’s some exciting work being done in the field of gene splicing, but RP is so complicated that a cure just isn’t a helpful thing to focus on. And clearly, if there was something I could do about my condition, I would’ve tried it (or, it could be, I just don’t want to submit myself to a treatment that would take away my quality of life).

At the end of the day, we’re all just human beings, trying to be seen and understood for who we are. Keeping in mind the two mindsets of avoiding patronizing and asking about preferences will never steer you wrong. As Brene Brown often says, “I’m not here to be right, I’m here to get it right.”