While young women around the world are stepping into jobs, shaping their futures, and embracing independence, most in India remain tethered to the age-old choreography of preparing for marriage. Why does a society so proud of its progress still see a woman’s prime years as a prelude to her wedding day rather than a gateway to her career? This stark contradiction is just one of the many themes explored by economist and Nobel laureate Abhijit Banerjee in his latest book, Chhaunk: On Food, Economics, and Society.

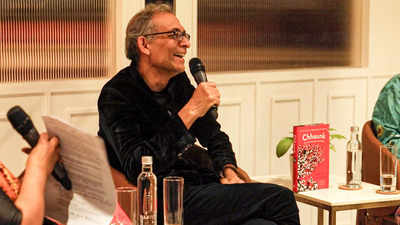

In conversation at a recent event at the Quorum in Gurgaon, Banerjee delved into the intertwined worlds of culture, economics, and society through the lens of food.

The Nobel laureate, who has previously authored the well-known Cooking to Save Your Life, as well as academic works like Poor Economics and Good Economics for Hard Times (co-written with his wife Esther Duflo), is known for making complex ideas accessible through his lucid writing. Like Amartya Sen, Banerjee’s reputation rests not only on his expertise in mathematical economic models but also on his deep engagement with development issues, philosophy, and societal structures.

The book is named after the tempering of dishes with spices and condiments, or ‘Chhaunk,’ It is a foundational process in Indian culinary traditions, celebrated across regional cuisines under various names. In Punjabi, it is known as Tadka; in Hindi, Chhaunk; in Bengali, Phoron; and in Telugu, Taalimpu, among others.

During the session, when asked why he chose the term ‘Chhaunk’ instead of the Bengali ‘Phoron,’ Banerjee explained that ‘Chhaunk’ feels more onomatopoeic. The word instantly evokes the sound of curry leaves, whole spices, or other ingredients sizzling as they meet hot oil when tempering a dish.

From academic journals to the kitchen

What led an economist of Banerjee’s stature to write a cookbook? He admits it was driven by his love for food and the unexpected opportunity provided by the COVID-19 pandemic. During the lockdowns, Banerjee found himself experimenting in the kitchen, turning memorable meals and intriguing recipes into stories.

In his book, each recipe is paired with anecdotes from Banerjee’s life and reflections on social issues, from caste and migration to economic inequality, much like a memoir.

Revisiting the role of women through Chhaunk

Banerjee’s reflections on food and society also tie back to his broader observations on gender roles in India, a theme central to Chhaunk. He cites his mother, economist Nirmala Banerjee, whose work highlights the societal pressures that keep young Indian women out of the workforce and confined to domestic spaces. Banerjee’s essays explore how these norms affect not just women’s lives but the economic fabric of the nation.

Why India’s daughters stay ready for weddings, but stay out of work

Banerjee’s book explores a range of interconnected themes, including economics and psychology, culture and social policy. In one instance, he references a paper by his mother, Nirmala Banerjee, which highlights a notable exception among young Indian women compared to their peers in other developing nations. Unlike elsewhere, where young women often enter the workforce as they transition into adulthood, gaining skills, confidence, and independence, Indian women tend to stay at home, preparing for marriage.

He writes: “…at the age where young women the world over are joining the workforce—learning the work routines and the discipline, gaining the confidence to speak up for themselves, but also embracing the pleasures… Indian women are mostly at home, preparing to get married.”

Notably, this aligns with India’s troubling labor statistics: In 2022, the country recorded one of the world’s lowest female labor force participation rates (LFPR), ranking below Saudi Arabia.

Labor Force Participation Rate, Female (2022)

Source: Labor force participation rate, female (% of female population ages 15 plus; modeled ILO estimate, 2022)

Why does India rank low? The underlying reason, the book highlights, is the societal expectation for women to confine their sexuality within a socially sanctioned, ideally monogamous, marriage. This creates a strong pressure on parents, who worry that their daughters might jeopardise these norms if they work outside the home, spend nights away, or meet someone deemed unsuitable for marriage. As a result, families feel a compelling incentive to marry off their daughters early, minimising the perceived risk of deviation from these expectations.

Basic income guarantee: A safety net or a double-edged sword?

In another chapter of his book, Banerjee delves into the concept of income guarantees, focusing on the idea of a Universal Basic Income (UBI). UBI is a policy proposal where every individual, regardless of employment status or income level, receives a regular, unconditional cash payment from the government. Proponents argue that it simplifies welfare systems, reduces poverty, and provides a safety net in an increasingly unpredictable economic landscape.

Banerjee explains, “By making it (income) universal and unconditional… we remove the incentive for people to exaggerate their poverty, say, by working less.” The goal is to bypass the complexities and inefficiencies of targeted welfare programs, where recipients often need to prove their eligibility.

He further elaborates on the challenges of targeted aid in developing countries. Evidence suggests that concerns about “strategic laziness”—the fear that free money disincentivizes work—are largely unfounded. However, people often conceal their true earnings, for example, by opting for cash payments to avoid scrutiny. This complicates targeted government programs aimed at helping the poor, as these systems frequently leak funds to the non-poor. Ironically, the additional checks and bureaucracy intended to prevent such leaks end up excluding a substantial portion of those who genuinely need assistance.

Banerjee contrasts this with universal, unconditional programs like UBI, which eliminate the errors of exclusion by providing benefits to everyone. However, this approach has its drawbacks. By distributing resources to many who don’t require them, it dilutes the amount available to those who truly need financial support, potentially reducing the overall impact on poverty alleviation.