Cagkan Sayin/Shutterstock

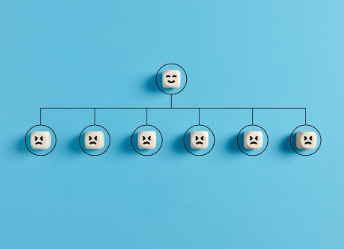

Employees are stressed, and part of the problem lies with rookie managers thrown into their new role with little or no training, according to a new poll. A sizeable number of U.S. and Canadian workers want to change teams or leave their employer so they can flee those managers, it found.

With no training in decision-making, running a meeting or knowing how to defuse conflicts, a manager can harm even a well-oiled team, creating inefficiencies and low morale or making employees want to run for the door, according to an Oji Leadership Poll of 2,066 workers by Harris Research.

Asked about their experience with first-time managers, 897 full-time U.S. workers reported the following:

- 41 percent said they were stressed or anxious about reporting to work.

- 34 percent wanted to leave the organization.

- 31 percent wanted to change managers by changing jobs or teams within their company.

- 31 percent lost confidence in their company overall.

Even a star player promoted to manager needs training.

[Check out 6 Tips for Training People Managers]

Linda Hill is a Harvard Business School professor, chairs the school’s leadership initiative and is co-author of the bestseller Being the Boss: The 3 Imperatives for Becoming a Great Leader (Harvard Business Review Press, 2019). Her work underlies Oji’s learning program for new managers.

“In my research, I’ve seen how strong individual contributors are often promoted to management roles with little or no leadership training, with a ‘sink or swim’ philosophy,” she said. Some rookie managers may be seasoned workers struggling in their new role “because we don’t help people much later in their careers,” Hill said in a statement about the findings.”

It’s no surprise that these untrained leaders often struggle in many areas, dragging their teams down with them in the process,” she said.

“Very few people look at the process” of becoming a manager, she told SHRM Online. “Even if you’re going to be really, really good at it, the transition is still really hard. … They are going to have missteps.”

Jen Jortner Cassidy, director of consumer success at San Francisco-based Oji, recalled in a LinkedIn post her experience as a 17-year-old manager when she was made head cashier at a grocery store.

“[I] acted like I was some kind of badass girl boss. I had no training to take on the role, I had just been an overachiever in that high school job that I took way too seriously. Reflecting on it now makes me want to apologize to everyone who encountered me as a colleague,” she recalled, adding, “Any organization who is promoting from within owes it to their new managers to provide the training and support that they need. That responsibility starts with the manager themselves and trickles down all the way to those who will be led by the new manager.”

What Employers Can Do

The biggest skills gaps for first-time managers: providing quality feedback, handling difficult situations, reducing conflict within teams, running a productive meeting and making decisions.

For example, learning to delegate is a common issue for new managers, said Paul Tripp, senior executive coach at Boston-based AceUp, a company specializing in coaching and leadership training.

This can be hard for the former individual contributor.

“They have to learn to trust, and they have to learn to accept a product they didn’t develop,” and this is especially challenging for star employees, Tripp said.”It’s important for organizations to think about how people go from the change of leading themselves to leading others and some of the pitfalls new managers are experiencing,” such as time mangement, imposter syndrome or how to transition from being a subject matter expert to a leader.

In a statement about the findings, Matt Kursh, CEO and founder of Oji, noted that “it’s no surprise that these freshly minted managers have anxious teams that want to quit; the managers are unskilled at decision-making, cultivating good communications, coaching people to success, and a range of other universal leadership skills.

“The good news is they can all be mastered, step-by-step.”

Have a Process

“Have a step-by-step process that helps [the new manager] practice and gain skill over time,” Kursh said.

Simply having been around good managers doesn’t necessarily instill the qualities needed to take over a team, he noted, any more than simply watching a surgeon perform 1,000 surgeries makes one a skillful surgeon.

However, sending new managers to an eight-hour workshop and expecting them to come back with the necessary skills is unrealistic, Kursh pointed out.

“Nothing magical can happen in those eight hours that makes you a good manager. There needs to be a social component where you interact with real humans” to have discussions, ask questions or role-play, he said.

Becoming a manager “is a head, heart and hands deal,” Hill said. “You have to help them understand how to manage-what are the roles, what are the responsibilities. Don’t assume they know. Do your research to understand what’s really key for the new managers in your context and help them get a sense of what that is.”

Consider Mentoring and Peer Coaching

People are social animals, Hill pointed out, and peer coaching and mentoring can be useful approaches.

In coaching new managers on handling difficult employee conversations, you teach them “it’s not so much about what [they] say [but] asking open-ended questions, being curious, leaning into the narrative of others,” Tripp said.

Coaching is an opportunity, he added, to talk about roles and be realistic about realigned responsibilities. The new manager may not realize they will need to manage their time differently than when they were an individual contributor.

Create a Safe Place to Talk

It can be helpful to create a safe space for new managers to talk about where they feel they are weak without fear of being seen as “the promotion mistake,” Hill said. It can be particularly difficult for stars accustomed to being “A” players who suddenly are “C” players because they haven’t yet mastered the managerial role.

Group coaching sessions of 10 to 15 new managers, led by a third party, can offer a safe place to ask questions and learn from each other on a specified topic, Tripp said. A TED Talk or article shared ahead of the session could be used to spark the discussion.

Use Assessments

“Assessment is critical” in evaluating people manager potential, Tripp said. An assessment should consider the individual’s strengths and what needs attention. What is their communication and leadership style? How do they handle conflict?

“It allows for a conversation to take place,” he said.