by Robert A. Scott

Elnur/Shutterstock

Campus leaders must anticipate, monitor, and manage risks. Pundits, politicians, and some within higher education itself describe the challenges to the enterprise and the changes needed. But campus leaders, presidents, and trustees, must be prepared even if a specific risk is not known in advance.

Last year, freshman student enrollment declined by 16 percent and overall enrollment fell by over 560,000 students. Budget deficits totaled more than $120 billion and over 500,000 employees lost their jobs. Many others had their salaries cut or experienced furloughs. Colleges and universities have eliminated degree programs and departments. Some have suspended admission to doctoral programs. More and more institutions are exploring the idea of a merger or other forms of collaboration in order to reduce expenses and maximize net revenue.

In addition to external forces, universities have paid millions of dollars in legal fees related to settlements for sexual abuse cases. One of the latest is the University of Southern California’s $1.1 billion resolution of 710 cases brought against the University’s former gynecologist.

With legal settlements, declining numbers of high school graduates, changes in the college-going behavior of those who do graduate, reductions in the number of international student applicants, and other challenges induced by demographics, economics, technology, and scandal, it is time for boards of trustees to ensure that their risk management tools, policies, protocols, and procedures, are up to date.

The Design of the Risk Assessment Matrix

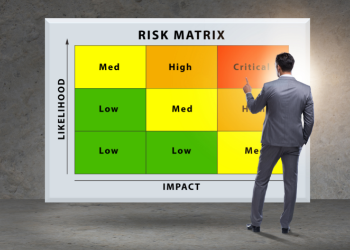

Risk assessment and management are aided by the use of a matrix that identifies categories of risk, the probability of each risk happening, and the severity of consequences for each risk. The risks to be identified include those that are related to operations and safety, including programs with unique risk potential; legal and regulatory compliance; financial operations and loss control; information systems security; labor and employment matters; and reputation. These categories are developed further below.

The matrix is a tool for management and the Board of Trustees Audit Committee to monitor routinely. It also can be referenced when discussing scandals, accidents, and other noteworthy events at other institutions. It is important to consider the whole landscape of higher education and society and not focus solely on the home campus.

Risks can be the result of human error, illegal or unethical behavior, or external factors. The goal of the matrix is to help anticipate, monitor, and manage potential risks, reduce workplace accidents, and ensure proper oversight. As risks are not static, the matrix should be reviewed and updated routinely.

The probability or likelihood of each risk identified is labelled as (1) almost certain, (2) likely, (3) possible, (4) unlikely, and (5) rare.

The severity of consequences for each risk is labelled as (1) insignificant, (2) minor, (3) moderate, (4) major, and (5) catastrophic.

For each risk, it is important to identify (1) internal management oversight, (2) the relevant institutional policy or procedure statement, (3) any special program initiative, (4) the insurance that would cover an event, and (5) the outside professional providing oversight, including audit, legal, vendor, etc.

With the likelihood of risks on the left-hand side of the matrix and the severity of the consequences on the horizontal axis, we can create cells to indicate each risk as high, moderate, or low in terms of impact.

The Use of the Matrix

The matrix is most frequently used by the president and senior staff and at least quarterly by the Board of Trustees Audit Committee as a means of anticipating undesired outcomes. It can be used and updated along with “table-top” exercises to consider how the executive team, and others, would respond to a bomb threat, a student sit-in, or other unusual event. It also can be used and updated when the team discusses a disturbing, scandalous, or violent event at another campus by asking “What can we learn from their experience?” “Could something similar happen here?” “Why and where?” On most occasions, it makes sense to include campus experts in the discussion, in addition to administrators, whether they be faculty in emergency management, business operations, public health, and psychology, or staff in facilities, student life, community relations, etc.

There are five main categories of risk.

*Business or economic model risks include tuition dependency, the use of remote teaching and learning, endowment returns, recruitment and retention strategies, cash monitoring, position control, and related elements of revenues and expenses. Most colleges do not have much flexibility when it comes to generating new net revenues. Many also have high fixed costs. Senior officers and trustees should be discussing “What if?” questions routinely.

*Reputation risks include those related to brand or image management, campus safety, student activism, and related risks vulnerable to the 24/7 news cycle and broadcasting by social media. Good reputation management requires prompt, clear, and accurate communications both on and off-campus. It is good to have positive working relationships with elected officials, editors and reporters, and other opinion leaders in the nearby and statewide communities.

*Operating model risks include those related to the adequacy of processes, people and training, and the systems that affect the ability of the institution to operate efficiently. These include operational efficiency third-party vendors, whether food service providers or construction firms; institutional and programmatic accreditations; facilities and asset management; business continuity and crisis management; human resources, data management; and cybersecurity. The C.F.O., chief administrative officer, and head of IT are essential to these discussions, but alumni and friends from select businesses, including the institution’s audit firm, can be especially helpful.

*Enrollment supply risks are those related to immigration and federal policies, higher education policies and priorities in other countries, alternative opportunities for the college-going population, and the specter of student debt on college attendance. Some campus leaders find it helpful to include faculty in demographics or a local school superintendent in such discussions.

*Last, but not least, are compliance risks. These include local, state, and federal regulations, funded research expenditure rules, academic and financial fraud, and related items. The institution’s legal advisor can be a helpful supplement to any campus legal expertise.

Updating the Matrix

The rapid change in public health protocols, family and community economics, college-going behavior, immigration policies, teaching modalities, and enrollment trends exacerbated by COVID-19 illuminate why it is essential to keep risk management tools up to date. Not only did new risks become apparent but also the need for collaboration among offices across the campus became essential. Isolation and silos are out.

The risk management matrix is a visible display with multiple dimensions, including category of risk, likelihood of risk, and severity of consequences of the risk. It should be used to spur discussion of enterprise risks, perhaps by focusing on one category of risk at each audit committee meeting. Another technique is to study an event at another institution and discuss whether and how a similar event could occur on your campus. The matrix will evolve over time, always a teaching tool for good governance and oversight.