India’s higher education system reveals a significant tale of regional disparity. The latest Annual Status of Higher Education (ASHE) 2024 report, jointly released by Deloitte and the Confederation of Indian Industry (CII), exposes a glaring divide between the northern and southern states. While southern powerhouses like Tamil Nadu, Kerala, and Karnataka surge ahead with impressive Gross Enrolment Ratios (GER) and robust institutional frameworks, northern states like Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and Rajasthan are left floundering with lower enrolment rates and inadequate infrastructure.

Numbers never lie, they say. Tamil Nadu’s GER of 47% stands in stark contrast to northern states that fall below the national average of 28.4%, as noted in the ASHE report. These figures reflect a pressing need for improvement in educational access and quality. The situation is particularly dire in rural northern regions, where a chronic shortage of qualified educators and inadequate facilities keeps higher education out of reach for countless students. This lack of access and entrenched inequity widen the chasm between the two regions, underscoring the challenges in creating balanced educational opportunities across the country.

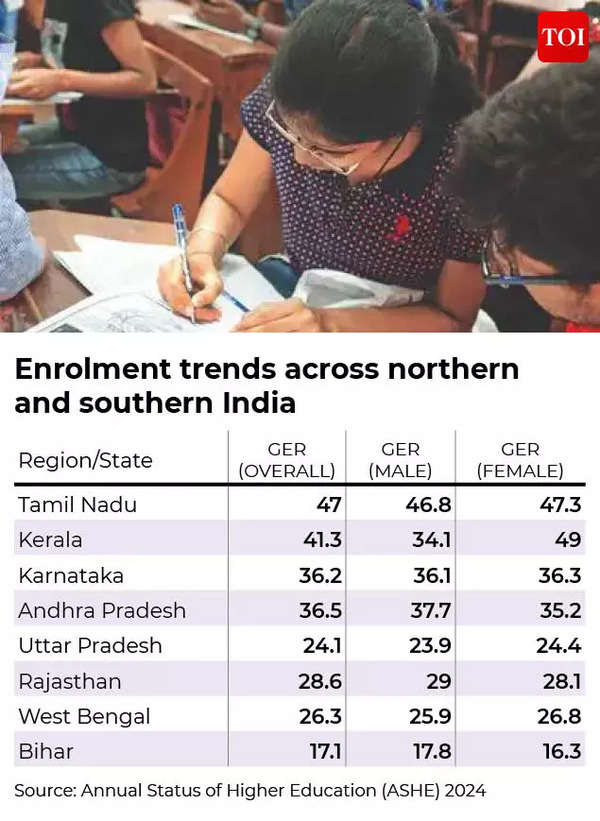

Differences in Gross Enrolment Ratio (GER) across northern and southern states

Gross Enrolment Ratio (GER) is a key indicator of higher education penetration. While southern states like Tamil Nadu (47%) and Kerala (41.3%) lead in GER, northern states like Uttar Pradesh (24.1%) and Bihar (17.1%) fall significantly behind.

GER in southern states reflects better access to higher education, influenced by factors such as proactive policy frameworks, institutional density, and cultural emphasis on education. Northern states face challenges in bridging the gender gap and improving overall enrolments, particularly in rural areas.

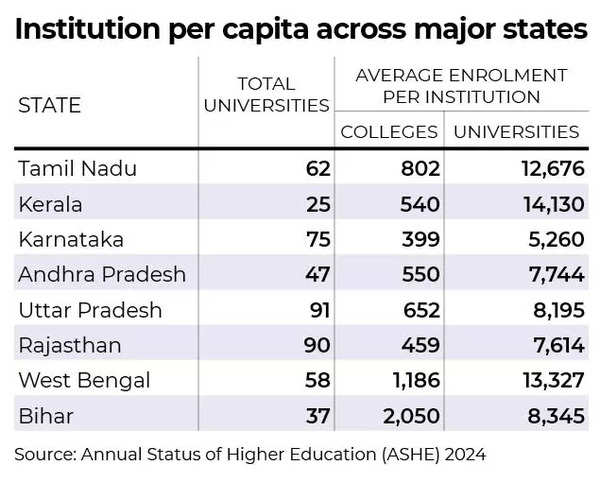

Institutional density per capita

In terms of infrastructure and institutional density, ‘higher education institutions (HEIs) per capita’ provide an insight into access. Southern states generally have higher institutional density, while northern states, despite large populations, lag in per-capita college availability.

Tamil Nadu and Karnataka showcase a strong institutional network, with a mix of private, government, and deemed universities, contributing to their higher GER. In contrast, Bihar and Uttar Pradesh need significant investments in higher education infrastructure to meet demand.

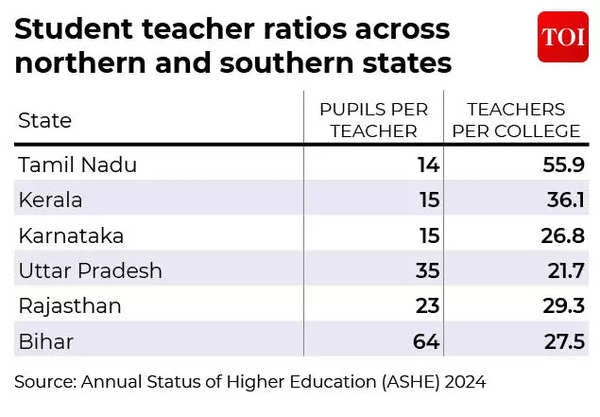

Pupil-Teacher Ratio (PTR): North vs. South

Southern states maintain better PTR and faculty availability, enabling personalised education and improved learning outcomes. Northern states like Bihar and Uttar Pradesh struggle with faculty shortages, leading to overcrowded classrooms and subpar academic engagement. Here’s an overview of a few of the major states.

Speaking to TOI, Kamlesh Vyas, Partner at Deloitte, acknowledged the issue of faculty availability, while recommending a balanced approach, “Filling vacant faculty positions is essential, but it’s equally important to use innovative teaching methodologies. For instance, leveraging technology to provide lectures from expert professors can complement local faculty and address shortages.”

He also suggests long-term industry-academia partnerships to improve curriculum relevance and faculty training programs like Madan Mohan Malaviya Faculty Development Programme to uplift teaching standards.

How Policy Intervention Bridges Regional Disparities in Higher Education?

The National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 serves as a roadmap to address regional inequalities in India’s higher education system. By focussing on infrastructure, inclusivity, and innovation, the policy aims to create equitable opportunities for students across the country. Here’s how NEP 2020 seeks to bridge these gaps.

Increasing institutional density: Expanding access to higher education

One of the key challenges in northern states is the limited availability of higher education institutions (HEIs). To address this, NEP 2020 proposes the establishment of multidisciplinary HEIs in underserved regions. This initiative includes upgrading existing colleges to universities and setting up new institutions to ensure every district has at least one multidisciplinary HEI by 2030.

Vyas highlighted that institutional density in backward districts, particularly in northern India, remains a critical issue. He explains, “In some of the backward districts, there are no universities. One of the goals of NEP is to create at least one university in each district. Making it closer to where the students are is going to be important.” This intervention can hyper-localise education access, reducing the distance students need to travel for higher education.

By focusing on northern states like Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and Rajasthan, where the college-per-capita ratio remains low, this intervention aims to improve accessibility and encourage enrolment, especially in rural and semi-urban areas.

Improving GER: Aiming for 50% growth by 2035

The introduction of the NEP was set with an ambitious goal of increasing India’s Gross Enrolment Ratio (GER) in higher education to 50% by 2035. TOI spoke to AR Ramesh, CEO of the TeamLease Degree Apprenticeship Programme, about the NEP 2020’s goal of achieving a 50% gross enrolment ratio (GER) in India by 2035, up from the current 28.4%.

When asked if this target was overly ambitious, he dismissed the notion, explaining, “The government is doing everything possible to achieve this goal.” He further highlighted initiatives like the micro-credentials framework and Apprenticeship Embedded Degree Programs (AEDP), which allow students to earn and accumulate credits through short-term courses and diplomas, making education more modular and accessible.

Concluding on a positive note, he said, “I believe the gross enrolment ratio will rise significantly to achieve the 50% target even before the 2035 timeline.”

Reiterating similar views, Vyas said that the target of attaining 50% national gross enrolment ratio is aspirational but not unrealistic.

Here are some of the key strategies initiated by the union government in the last few years, which are likely to make a difference in the GER parameter in the longer run:

•Promoting online and distance education: Expanding virtual learning opportunities to reach students in remote areas, while at the same time increasing awareness as to its acceptance in career prospects and further education.

•Vocational programs: Integrating skill-based learning to attract students who prefer practical training over traditional degrees.

•Flexible credit systems: Enabling students to complete their education in stages and across multiple institutions, thereby reducing dropout rates. This focus will particularly benefit regions with low GER, such as Bihar and West Bengal, while sustaining the progress in states like Tamil Nadu and Kerala.

Focussing on gender and social equity

To address disparities in access for women, Scheduled Castes (SC), Scheduled Tribes (ST), and Other Backward Classes (OBC), NEP 2020 prioritises inclusivity.

A significant component of accessibility is providing financial assistance and fair opportunity for people beginning their education. Financial aid and preparatory programs enable under-represented groups to compete on equal footing. In northern states, additional incentives and support systems are aimed at achieving gender equality, particularly in Haryana and Uttar Pradesh, where female enrolment is lower than male enrolment.

Hyperlocal implementation of digital initiatives

With physical infrastructure often lacking in rural and underserved regions, NEP 2020 emphasises the use of technology to expand access. Key initiatives include:

•Development of digital platforms: Creating resources like the National Digital Library and e-learning modules to support students across the country.

•Hybrid learning models: Encouraging a blend of online and offline learning to overcome limitations in physical capacity.

This is especially beneficial for states like Rajasthan and Jharkhand, where traditional infrastructure gaps can be offset by digital solutions.

What the ASHE 2024 report highlights

While southern states lead in higher education metrics, their northern counterparts face challenges that require sustained policy attention. With the NEP 2020 as a guiding framework, addressing these disparities is vital for creating an equitable and accessible higher education system across India. The path forward requires a focus on expanding infrastructure simultaneously working on improving the quality of pedagogy, and enabling digital solutions to bridge the divide.