In the last couple of years, te.gism, the “fruit with a dot in its name”, has caught the imagination of wine lovers in the Northeast who fancy non-grape elixirs. Also known as the Himalayan cherry (Prunus jenkinsii), this fruit that grows in the jungles of Meghalaya’s Garo Hills remained virtually unknown until botanists documented it less than a decade ago. Today, it is cultivated by farmers in the region for the state’s burgeoning fruit winemaking industry.

Lyang B. Sangma was understandably on edge when his te.gism product was among six exotic fruit wines and meads — alcoholic beverages made by fermenting honey — chosen by the Meghalaya Farmers Empowerment Commission (MFEC) to showcase at the Vinexpo India 2024 in Mumbai this September. “I had my heart in my mouth whenever an expert or connoisseur sipped the te.gisim wine and rolled his or her tongue over it. The reaction from almost all of them was that my product has possibilities beyond my hometown of Tura and other parts of Meghalaya,” says the entrepreneur.

Situated on low hills, Tura is the economic and administrative hub of the western part of Meghalaya, dominated by the Garo community, and about 300 km west of state capital Shillong. Most Garo families are used to brewing bitchi, a smoky rice beer made from local sticky rice. After observing elders do the fermentation process, Lyang began experimenting with other grains and wild fruits. He concentrated on exotic fruit wines, producing them mostly for consumption among family and friends and for gifting during Christmas and other festivals. Sensing an opportunity, he went commercial with his Dura Wines in 2021, a year before another entrepreneur, Keenan Marak, from the Garo Hills launched 7 United, a canned, carbonated bitchi.

17 winemakers go commercial

Lyang’s winery, set up with a machinery grant of ₹25 lakh from the Shillong-headquartered North East Centre for Technology Application and Reach, has since been producing wines from seasonal fruits such as gooseberry, pineapple, cherry, silverberry, bayberry, black plum, and jackfruit, apart from the traditional bitchi in a bottled avatar. While the bayberry offers a sweet note, the jackfruit wine is pungent and an acquired taste. The demand, however, has been more for the dark red te.gism, almost equalling that for the blood-red te.patang that fellow Tura-based winemaker Pecindha K. Sangma has been churning out under her Asame brand.

Te.patang is the Garo name for the sweet and sour blood fruit (Haematocarpus validus). “The popularity of this fruit encouraged me to make wine from it along with other fruit wines like strawberry, peach, plum, pear, jamun, and mulberry. I produce an average of 40 litres of season-based fruit wines a month. What has also caught the imagination of consumers in Meghalaya and elsewhere is the blue wine made from the butterfly pea flower,” Pecindha says.

Asame’s blue wine made from the butterfly pea flower.

From being an occasional winemaker, Pecindha transitioned to producing wines on a commercial scale from her home in 2023. Villagers collect honey for mead from the forests, much like they do fruits. “People here make a tea-like beverage from the butterfly pea flower. I thought of infusing it with honey wine and through trial and error and with advice from experts, I found the right balance with no added sugar,” she says. Many of these entrepreneurs have made the switch following periodic consultations with Priyanka Save of Himachal Nectars, roped in by the MFEC as the official training partner for certification courses.

Today, Meghalaya has about 30 fruit winemakers (mostly in Shillong and Tura), of whom 17 have transitioned to commercial production with modern, scientific equipment. (Traditional rice wine makers are in the thousands.) All but three of the 17 have established wineries and started branding their wines over the last two years; the other three are in the process of scaling up their facilities. The average cost of setting up a winery of 5,000-litre capacity is ₹50 lakh, excluding the land and buildings. About 400 families, including winemakers, farmers, and farm workers, are directly or indirectly employed by the licensed wineries.

Non-indigenous fruits like orange, strawberry and pineapple are also used in wine-making in Meghalaya.

| Photo Credit:

Ritu Raj Konwar

Back to the beginning

The shift to commercial winemaking may have happened only in the last two to three years, but the process to streamline the industry has taken two decades. It began with Michael Syiem of the Shillong-based Forever Young Club organising the city’s first wine festival in 2004 to showcase an array of wines made from indigenous fruits and vegetables. “The annual event made our people take fruit winemaking seriously. Millennials found the exotic wines cooler than expensive grape wines, which they associated more with the older generations. The push came after our commission, the only one of its kind in the country, was established in 2019 to represent the voices of farmers and formulate policies and programmes for agriculture, food processing, and value chain development,” says B.K. Sohliya, chairman of the MFEC.

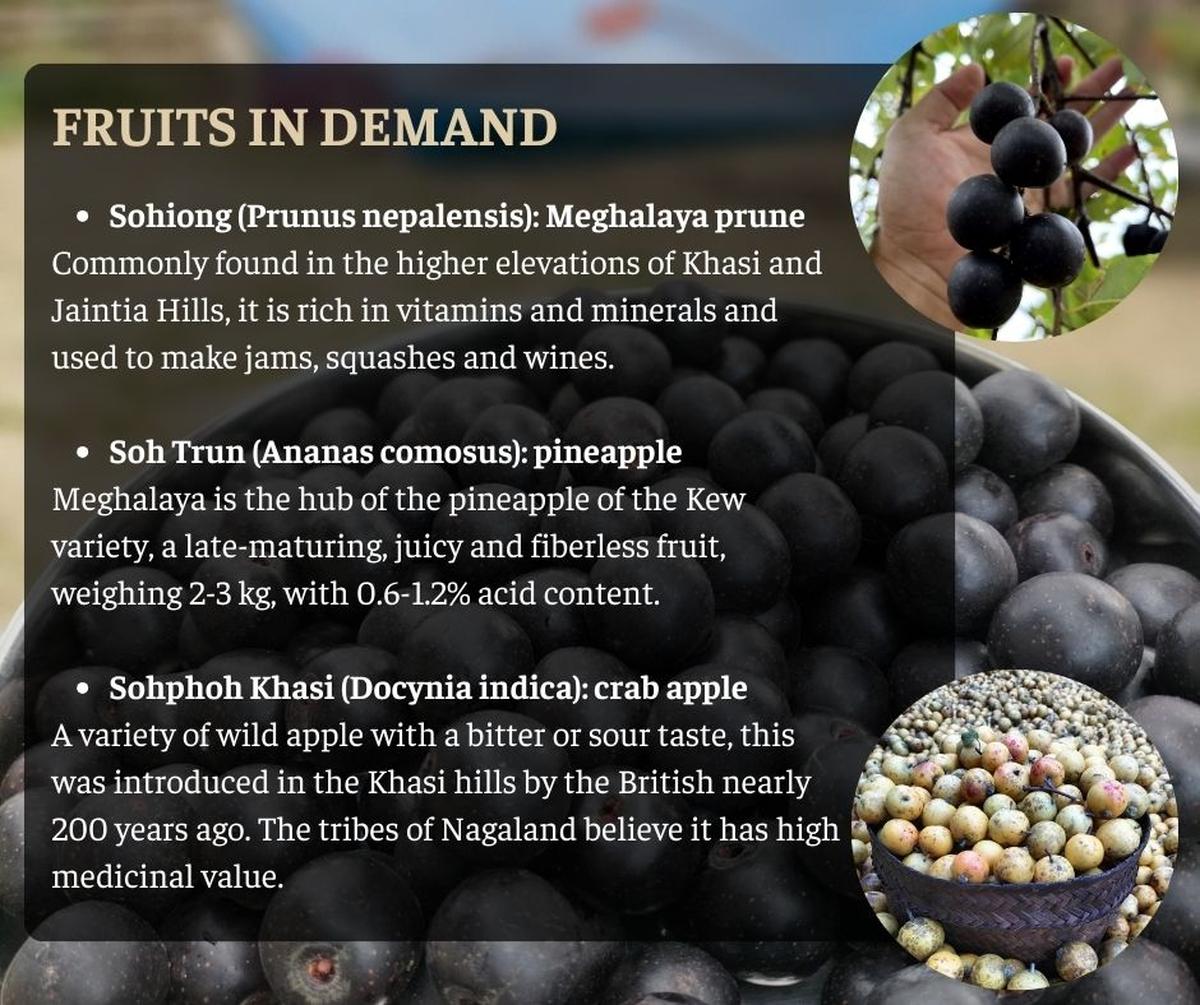

Unlike grapes, which have wine-grade varieties, Meghalaya’s indigenous fruits such as sohiong (Prunus nepalensis), sohphie (Myrica esculenta), sohshang (Elaegnus latifolia), sohphlang (Flemingia vestita) and sohphoh khasi (Docynia indica khasiana) grow naturally, barring the few introduced species such as strawberry, pineapple and orange that grow in plantations. All are single-variety; what’s consumed as fruit is also used for making wine.

Many of these wild fruits are protected in the sacred groves of Mawphlang, a village about 25 km southwest of Shillong. No one is allowed to take anything — not even a fallen leaf — from the groves that became a tourist attraction after a British army officer set up India’s first winery in the village in 1947.

Capt. Harold Douglas Hunt, considered the father of wine in Meghalaya, settled down in Mawphlang and obtained a license to make his Mawphlang cherry wine and brandy a household name in the state. He mobilised villagers to collect sohiong and other wild fruits from beyond the sacred groves, and created a well-oiled ecosystem wherein local farmers, producers, and artisans coordinated to sustain the winery until it ceased operation in the 1980s after his death.

Ritual monoliths at the entrance of the Mawphlang sacred forests in Meghalaya.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

Forty years later, Capt. Hunt’s house — a deep green cottage barely 2 km from the sacred groves — is abuzz again. Hunt’s grandson, Andrew Nongdhar, has overhauled his winery to produce the “old popular wine” in new bottles “as soon as possible”. “Many were inspired by my grandfather to brew wines from fruits and vegetables such as ginger, but winemaking remained a small-scale activity until recently. Entrepreneurship, a change in mindset, and a proactive government combined to help the winemakers transition to commercial production. Failing to capitalise on this trend would have been an injustice to the man who started it all,” he says.

Government initiative

In September 2020, the Meghalaya Excise Rules (Assam Excise Rules 1945) were amended to legalise home-made wines and provide licences to local winemakers to go commercial. “Chief Minister Conrad K. Sangma and a team of officers like our former chairman, K.N. Kumar, played a major role in giving shape to the fruit wine industry in Meghalaya. From five licensed fruit winemakers three years ago, we have 17 today — the second-highest in the country after Himachal Pradesh, which has 22,” says Sohliya.

The Meghalaya government imposes no VAT on fruit wines compared to 4%-53% VAT in other Indian states. The only levies are an ad valorem of ₹100 per case (12 bottles) and a retailer’s lifting fee of ₹10 per case.

The government also organises ‘Beyond the Grape’ shows to introduce wine lovers from elsewhere to Meghalaya’s fruit wines, while the MFEC has established the North East Fruit Wine Incubation Centre, a pioneering training facility for winemakers with an installed capacity of 1,000 litres per cycle, at the Institute of Hotel Management, Catering Technology and Applied Nutrition on the outskirts of Shillong. Since its establishment in 2023, the institute has trained 137 people, mostly from the Northeast, in the “art of winemaking that is mostly science” as Sohliya says — from fruit to bottled beverage in 90 days.

A restaurant that offers wine for tasting in Shillong.

| Photo Credit:

Ritu Raj Konwar

According to Rajesh Swarnakar, professional wine and spirit taster, the quality of Meghalaya’s fruit wines has improved markedly in texture and taste, with a better balance of sugar and alcohol (10% ABV). “Currently, Meghalaya’s fruit wines have some distance to catch up with fruit wines from Himachal Pradesh, where they are mostly made from apples. But then, fruit winemakers in Himachal have been in the business for years with good government support while the Meghalaya government has become involved recently,” he says.

The popularity of Meghalaya’s wines is growing, believes Swarnakar, as more tourists seek them out from the shelves of liquor outlets in Assam and Meghalaya. The average cost of a 750 ml bottle of fruit wine is ₹600.

Checking farm waste

The winemaking ‘renaissance’ in Meghalaya has also entailed taking homemakers, farmers and entrepreneurs on exposure trips to the winemaking hubs of Maharashtra and Himachal Pradesh. One such farmer, Bording Ioannis Shylla, has set up the state’s largest winemaking unit (10,000-litre capacity) at Mawkyrwat, about 75 km southwest of Shillong, to produce and market his brand, Damad, with his winemaker wife, Meldorah Wanniang. The couple has acquired 60 acres of land for farming, and they also coordinate with nearby villages for bulk supply of fresh fruits.

Farmer Bording Ioannis Shylla (in white) at his winemaking unit in at Mawkyrwat.

Says Sohliya: “One of the factors behind the stress on winemaking was to check the wastage of fruits and vegetables. Meghalaya’s terrain does not allow large-scale farming, and farmers here invariably cannot sell all they grow or collect from the jungles. Their fruits of labour often rot; the rate of wastage is similar to India’s average of 40% for fruits and vegetables throughout the supply chain.”

He adds, “Wastage has come down substantially with winemakers booking farms or trees a year in advance as a winemaker needs a tonne of fruit to produce 200 litres of wine. A farmer who earned ₹3,000 per sohiong tree now makes ₹15,000 a season, while kiwi, plum, peach, pineapple, orange, and jackfruit farmers have upped their income from ₹30,000 to more than ₹3 lakh per season. There has also been a shift from gathering fruits from the jungle to farming them.”

Agreements with farmers are fuelling urban wine startups such as Shillong’s Kynjai Wine launched by Dajied Shabong. “From procuring fruits from farmers and bottles from Mumbai to the final packaging, winemaking is a complex process, but rewarding for the soul. Our wines are on par with those produced elsewhere in India, if not the world. Things are moving fast in Meghalaya and we hope to upgrade from selling from home to supplying to stores in the Northeast soon,” says Shabong.

For Michael Syiem, acknowledged as the man who sparked the winemaking movement in recent history, the industry in Meghalaya is heading in the right direction. “The enabling atmosphere and the entrepreneurial drive of a few are making it possible,” he says.

rahul.karmakar@thehindu.co.in

Published – November 15, 2024 03:53 pm IST