All humans live different lives. An author spends days and months and years trying to write the perfect story to catch a reader’s attention, an artist fills canvas after canvas trying to paint his masterpiece, a lawyer studies case laws and hefty books to prepare for his next client, and an activist saves people, men, women, young and old, from the clutches of humans who should no longer be called a humans.

From traffickers to gamblers, an activist deals with them all, trying to save an innocent soul who got sucked into the vicious cycle and hole of crime and injustice. They spend months rallying for support, cry before the ‘people in power’ to take a step, and when nothing seems to work, they stream into action.

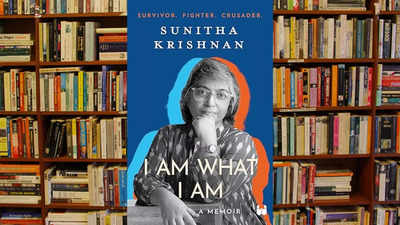

And one such activist is Sunitha Krishnan who in her memoir ‘I Am What I Am‘ has shared accounts, stories, details, and incidents that can send shivers down an ordinary man’s body.

And so, here we mention an excerpt from the book with due permission from the Publisher ‘Westland Books‘.

The shrill ring of the phone jolted me from my sleep. At 5 a.m., this could only be an emergency. It was the police. I could hear the worry in the man’s voice. I was to go right away to the railway tracks behind the Falaknuma railway station. I was ready in under five minutes; my team and I had the drill down pat. So I telephoned Akbar and asked him to bring Jaffer’s autorickshaw over. We left immediately. With the streets empty, we reached in about ten minutes. In the distance, I spotted a few policemen huddled together. It must be an abandoned child, I realised. The police wanted to hand her over to us, as they had many times in the past. I had streamlined this process over the last four years of doing this work. The Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection) Act, 2000 was just out, and while it was not yet properly implemented, it provided the legal framework for extending care and protection to children like the ones I served. Our homes for both children and adults were now functional. We had thirty children already in our home, and we had slowly begun to accept children from the newly formed Child Welfare Committee along with those who were referred by police stations.

Ours was the only home in the area, so the police, especially the ones in the Old City of Hyderabad, referred many cases to us. It was

always a big challenge to refuse children who had eloped or had been abandoned, but I was very clear about my mandate: I would only

take in children of women in prostitution, victims of rape and of sex trafficking and HIV-positive children. It was always a hard decision,

2 sunitha krishnan but we needed to optimise our limited resources and skills. My team may not have the academic qualifications, but they were trained well.

And with many of our own rescued women joining us, we had people with lived experience who intuitively knew what should be done. All

this had helped us evolve a comprehensive programme to cater to the needs of the children we served. Anybody who visited our home could vouch for the outcome of our interventions. To my mind, today would be one of those cases where the police just wanted to hand over the child and fulfil their responsibilities, and congratulate themselves for early-morning productivity. As I approached the police, I went over possible reasons for refusing them and the organisations I could refer them to instead. It was only when I was close enough to see their faces that I registered their horror and discomfort.

I peered at the child and drew in a sharp breath. There was blood all over. The girl, six or seven, maybe even younger, was alive and

breathing, though unconscious. The policeman next to me leant over, whispered something in my ear. I couldn’t make sense of it. I went

down on my knees and gently touched the child. She woke up, whimpering in pain. I reached out to pick her up. That’s when I realised her intestines were trailing out of her vagina. Her insides were torn through. She needed the hospital right away.

I gathered her up, one hand on her shoulder, the other supporting her bottom, and started running. The policemen, shaken out of their

stupor, ran with me towards Akbar, waiting by the auto. I asked one of them to get in and told the others to follow. At Osmania General Hospital, the doctors went still with shock when they saw the child. In seconds, though, their training took over, and they rushed her to the emergency ward. It was then that I began to talk to the constable who had accompanied me. He told me that one of the beat constables

had found the child at 4.45 a.m. near the railway tracks. The child appeared to have been gang-raped and thrown near the bushes. Maybe

they thought they had killed her. But the beat constable realised that the child was alive.

This constable, who was posted at the Chatrinaka police station, had sent several children to our home and had my number. His

presence of mind and humaneness were definitely greater than his love for duty and protocol. Very often, lower-rung policemen first

inform their senior officers and only then raise the alarm and alert agencies like ours. This, of course, means loss of precious time. In this

case, though, the intervention was prompt and the police action that followed was diligent. They had arrested six migrant workers, one of

whom was the father of the girl. He and his friends had assaulted the child in a drunken rage and left her for dead.

I am a deeply spiritual person. Over the years, my daily routine of prayers and meditation have helped me focus on the task at hand

without getting overwhelmed. But that day, if god had appeared before me, I would have killed them with my bare hand.