by Robert A. Scott

Tada Images/ Shutterstock

More than 450,000 students in higher education are undocumented. As such, they face hurdles related to affording and completing college that others do not. There are restrictions on their ability to enroll and limits on access to in-state tuition, state financial aid, driver’s licenses, and work authorization.

At a time when higher education is losing enrollment due to declining high school graduation numbers, reduced birth rates, and limitations on international student recruitment, undocumented students who live in the U.S. represent a substantial pool of potential candidates for colleges and jobs — and they have demonstrated their commitment and ambition. They represent an answer to the talent shortage so often lamented.

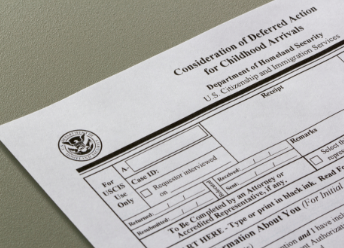

The terms undocumented and DACA are not interchangeable. The term undocumented applies to any person who lives or works in the U.S. without the legal protections of a citizen or a permanent resident. Nearly one-half have or are eligible for DACA status. DACA stands for Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, a 2012 Obama Administration Executive Order allowing people who were brought to the U.S. as children to legally live, go to school, drive, and work when certain criteria are met. It does not yet include a path to citizenship. The term “Dreamer” is derived from the proposed “Dream Act” introduced in Congress before DACA and is now used to describe those protected by DACA. The Dream Act has not been approved by Congress.

Neither undocumented nor DACA students are eligible for federal aid but can receive in-state tuition and state financial aid in certain states, including Colorado.

Nearly one-half of undocumented students in higher education identify as Hispanic, 25% are identified as Asian, and 15% are identified as Black. Over 80% attend public institutions. The five states with the most undocumented students are California, Texas, Florida, New York, and Illinois.

The average DACA person has lived in the U.S. for 22 years and, on average, is 28 years old. In recent years, over three-quarters of DACA recipients in the workforce (343,000) were employed in jobs designated “essential” by the Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS) Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency. The loss of DACA would result in the loss of 22,000 jobs every month for two years, or about 1,000 jobs each business day.

The great majority of DACA recipients have graduated from high school, and nearly one-half have attained at least some college education. Over 40% of DACA-eligible advanced degree students study in STEM fields.

Many colleges consider undocumented students the same as international students, thus they must compete for the limited aid available for such students. When undocumented students are considered domestic, they are more likely to receive a financial aid package. Almost two dozen states allow undocumented students to pay in-state tuition.

One of the most impressive programs for DACA students is the Immigration Services Program at Metropolitan State University of Denver (MSU Denver). It serves DACA and undocumented students with a goal to increase access, retention, and graduation rates for DREAMer students. They intentionally educate the campus and offer resources for students, faculty, and staff, creating what they call a “Dreamer Network” and providing “Undocupeers training.”

DREAMer students are active on campus, participating in various clubs such as debate teams and student government. They are widely regarded as good campus citizens and serious students, often pursuing graduate degrees following their undergraduate education.

At MSU Denver, 332 undocumented students studied last year under Colorado’s ASSET Law that allows eligible undocumented students to pay in-state tuition. The University has long been a leader in supporting undocumented students, offering undocumented Coloradans in-state tuition in 2012 before DACA was established.

DACA recipients are required to pay $495 to renew their protections every two years. To help them, MSU Denver has provided close to 130 grants to cover DACA renewal fees for students since 2017. The University has partnered with an immigration advocacy group to provide 15 additional grants in recognition of the 10th anniversary.

Long controversial in some quarters, on Oct. 5, 2022, a federal appeals court agreed with a July 2021 Houston court ruling that the DACA program is unlawful. The case was sent back to the Houston court.

Days later, the judge issued an order that extended the injunction and partial stay of the final rule. This means that U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Service (USCIS) will continue to accept and process DACA renewals and work permits for current DACA recipients until the Houston judge decides the future of the DACA program. While the future of the program is uncertain, Congress could act, but has so far not shown an inclination to do so.

On Oct. 31, 2022, DHS announced a final rule to continue the DACA program under the current policy. This rule means there are no changes for current DACA recipients or their ability to renew their status. New applicants are still not able to apply under the DACA program because of the July 2021 court ruling. Those who were granted DACA status before the court decision will continue to have DACA status if they renew it on time. USCIS will continue to accept the filing of new requests for DACA and employment authorization, but they will not grant these requests.

Those interested in the condition of higher education and the future of our country should do all they can to emulate Metropolitan State University of Denver and advocate for DACA and these deserving students.

Disclaimer: HigherEdJobs encourages free discourse and expression of issues while striving for accurate presentation to our audience. A guest opinion serves as an avenue to address and explore important topics, for authors to impart their expertise to our higher education audience and to challenge readers to consider points of view that could be outside of their comfort zone. The viewpoints, beliefs, or opinions expressed in the above piece are those of the author(s) and don’t imply endorsement by HigherEdJobs.