A shopper at Lincoln Market in Brooklyn, New York, on June 12, 2023.

Michael M. Santiago | Getty Images News | Getty Images

Inflation slowed sharply in June to its slowest pace in more than two years, translating to less of a pinch on the average consumer’s wallet thanks to price relief across categories like energy, groceries and housing.

Inflation measures how quickly prices are changing across the U.S. economy.

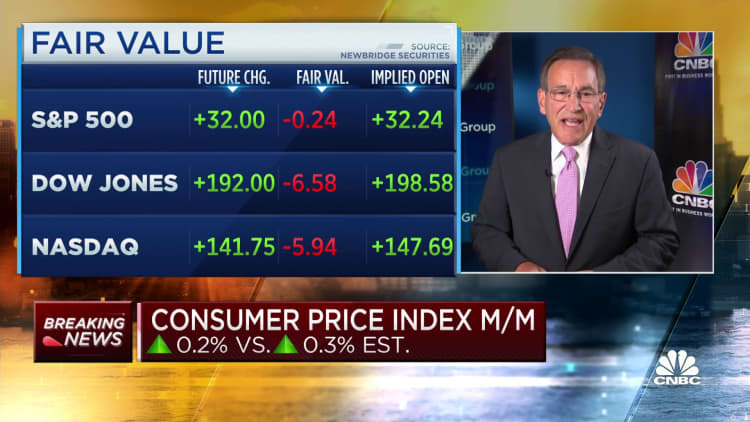

The consumer price index increased 3% in June relative to a year earlier — a slowdown from 4% in May, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The CPI is a key barometer of inflation, measuring prices of anything from fruits and vegetables to haircuts and concert tickets. June’s reading is the smallest 12-month increase since March 2021 — around the time when alarm bells started sounding about fast-rising prices in the pandemic era — and a significant pullback from 9.1% in June 2022.

The report “makes a strong case that inflation is headed back into the bottle,” said Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s Analytics.

Easing price pressures thus far are largely attributable to the fading effects of supply shocks caused by the Covid pandemic and the Russian war in Ukraine, Zandi said.

The decline in the inflation rate doesn’t mean household expenses have fallen in aggregate; it means they aren’t rising as quickly.

And that’s good news for consumers: The average worker’s earnings growth is now outpacing inflation, translating to an increase in their standard of living after two years of declines. Hourly earnings increased 0.2%, on average, from May to June after accounting for inflation, according to BLS data.

While inflation is on a downward trajectory, it remains above the Federal Reserve’s long-term target of around 2%.

“I think inflation is moving to a better place, but we’re not in the Promised Land of the 2% target,” said Mark Hamrick, senior economic analyst at Bankrate. “We know the journey is progressing, but it’s not yet over.”

‘Encouraging’ inflation signals moving forward

The inflation slowdown has been broad-based, Zandi said.

“It’s food, it’s energy, vehicle prices, the cost of housing is slowing,” he said. “Pretty much across the board, we’re seeing a moderation in price increases.”

Gasoline prices have fallen dramatically from a spike in the first half of 2022 that was a result of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Prices at the pump are down almost 27% in the past year, according to the BLS. They rose slightly — by 1% — from May to June.

Grocery price inflation is also down significantly from its peak around 14% last summer, which had been the highest rate since 1979. “Food at home” prices are up about 5% in the past year and were flat from May to June, according to the BLS.

But food and energy prices can be volatile. That’s why economists use a measure that strips out such categories to get a better sense of inflation’s trajectory going forward.

The measure — so-called “core CPI” — hit a 20-month low of 4.8%, according to Andrew Hunter, deputy chief U.S. economist at Capital Economics. And it’s “potentially even more encouraging than it looks,” as wholesale auction data for used cars points to a sharp decline in prices over the next couple of months, he said in a research note.

More from Personal Finance:

Other countries don’t have an issue with ‘tipflation’

How to protect your money from inflation

Why it’s nearly impossible to find a car for less than $30,000

The “core” measure also includes housing, which is the biggest expense for the average consumer.

The “shelter” index was the largest contributor to inflation in June, accounting for 70% of the monthly increase, according to the BLS. Shelter prices are up nearly 8% in the past year, but moderated from May to June. Economists say it’s a near certainty that housing prices will continue to fall through the second half of the year.

At the current pace of inflation, the core CPI metric should fall back to the target level by this time next year, Zandi said.

We know the journey is progressing, but it’s not yet over.

Mark Hamrick

senior economic analyst at Bankrate

“Notable” increases in annual inflation rates include motor vehicle insurance (up 16.9%), recreation (4.3%), household furnishings and operations (3.6%), and new vehicles (4.1%), according to the BLS.

However, several categories actually saw deflation — meaning consumers saw average prices fall — in the month from May to June, the BLS said. They include airline fares (which declined 8.1% in that period), which followed declines in April and May, too. There was also a 0.5% monthly decline in the “communication” index, which includes expenses such as phones and computer software.

Inflation is a ‘complicated phenomenon’

Inflation during the pandemic era has been a “complicated phenomenon” stemming from “multiple sources and complex dynamic interactions,” according to a paper published in May and co-authored by Ben Bernanke, former chair of the U.S. Federal Reserve, and Olivier Blanchard, senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics.

At a high level, inflationary pressures — which have been felt globally — are due to an imbalance between supply and demand.

It’s largely a three-pronged story in the U.S., said Stephanie Roth, senior markets economist at J.P. Morgan Private Bank.

The first is inflation among physical goods.

Consumer prices began rising rapidly in early 2021 as the U.S. economy reopened after its Covid-induced shutdown. Americans unleashed a flurry of pent-up demand for dining out, entertainment and vacations, aided by savings amassed from government relief, months of curbed spending and rock-bottom borrowing costs.

Meanwhile, the rapid economic restart snarled global supply chains. The supply of goods couldn’t keep up with consumers’ zest to spend. The result was fast-rising prices.

The second prong is war in Ukraine, which exacerbated backlogs in the global supply chain and fueled higher prices for food, energy and other commodities, said Roth.

The third is inflation for “services,” a category that includes housing and labor-intensive service businesses like restaurants and hotels.

Pretty much across the board, we’re seeing a moderation in price increases.

Mark Zandi

chief economist at Moody’s Analytics

As the economy reopened after the pandemic, businesses rushed to hire workers, and job openings surged to record highs. That demand tilted the job market in favor of workers, who had ample opportunities. They saw wages grow at their fastest pace in decades as employers competed to hire them.

That strong wage growth has nudged employers, especially labor-intensive service businesses, to raise prices to help compensate for higher labor costs, economists said. There are signs that labor dynamic is easing, though — which should put downward pressure on overall inflation.

The Federal Reserve has been raising borrowing costs aggressively since early 2022 to rein in demand among consumers and businesses, and ultimately help bring inflation back to its 2% annual target. The central bank is expected to raise interest rates at least once more.